| Response to Change |

|

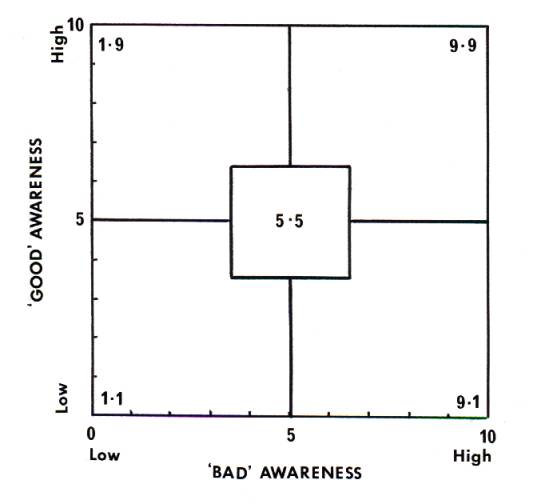

A brief practical treatment of common reactions,

whether of individuals or organisations when faced by change of an apparently threatening

nature. After a brief review of the origin of the common defensive reactions, sections

look at healthy and unhealthy ways of handling transition, whether for individuals or

organisations and institutions. The paper is a revised edition of an article originally

published in April, 1981. [1981, Revised 1987] * * * * * * * * * A clear understanding of individual and organisational reactions to change is an essential foundation for its effective management. The conceptual model outlined in this article is offered in the hope that it will encourage readers to use every situation as an opportunity to develop an increasing awareness of their own reactions to change, and also of the way people and organisations around them are responding. A Conceptual ModelUnderstanding of the process is greatly helped if we separate reactions into two independent parts, each varying in strength. The first. element could be described as awareness of benefit brought by the change. The second element is characterised by awareness of the bad things about it. Each element. can be given a scale from 0 to 10, and the two elements can be related at right angles and the square completed. Every point within this square now represents some combination of the two elements of awareness, representing a particular reaction of a particular person to a particular change at a particular point in time. There are five typical positions within the field. In the bottom left-hand corner (1.1) is the response of blissful ignorance, the point of no change, of inertia with almost no awareness of the needs for change, of its potential advantages or disadvantages. The next position can be described as idealised endorsement (1.9). Here at the top left-hand corner of the grid is the reaction which hears no evil, sees no evil and speaks no evil. Awareness of the benefits of the change is maximal and no objections are allowed. The voicing of any dissent is outlawed and deemed almost a personal affront or breach of loyalty. In the opposite corner (9.1) is the reaction of unrelieved opposition. The change is perceived as utterly bad. The person in this position cannot find a good word to say for the idea and will attack anyone who supports it. The proposed change raises a sense of threat, loss and anxiety which filters out awareness of any potential benefit which might have accrued. Holding the centre (5.5) is the position of conflicted ambivalence. There is some awareness of the advantages which the change might bring, but this is balanced by an equal and opposite awareness of the disadvantages. The final point, in the top right hand corner of the field (9.9) could be described as 'realistic integration'. This top corner is characterised by a commitment to stay with both the good points and the bad points, sustaining high levels of awareness of both and working realistically in the light of both advantages and disadvantages of the proposed course of action. However polarised, ambivalent or reactionary a given person's position may be, the individual is normally quite unaware of distortion and perceives the self as acting rationally, weighing up the pros and cons in complete touch with reality. Unfortunately very few people are so whole or 'together' that they can sustain a 9.9 position through any but the most superficial of changes. All change generates a certain amount of anxiety. For a given person different changes will trigger different levels or intensities of distress. A given change will trigger different levels of anxiety in different people. The amount of angst experienced depends to some extent on the significance, depth and extent of the change itself, but also on the level of unresolved, repressed anxiety held in by the unconscious of the person concerned and with which certain elements in the process may resonate. Every change is a little birth, a movement across a boundary from a known to an unknown, a temporary loss of security. In so far as a given change resonates with unresolved primal distress, just so far does the current situation become loaded with projected anxiety, as if the person is again facing birth with its life-threat, crushing, breathing difficulties, the cutting off of a life-support system and total loss of the known world. The defences used by the mind in order to avoid being overwhelmed by this primal distress are called into action again to deal with that material in the contemporary situation which threatens to bring the experience back into consciousness. These defences act as information filters, cutting out from awareness certain elements of reality. At a superficial level people lose concentration, day-dream, become selective in their memory, forget to turn up to a meeting, or even become ill, or accident-prone. The field of information may become polarised. Anxiety is lowered by denying any evidence that might conflict with the perceived position. A person may respond to a given change by feeling very threatened, angry fearful and only able to perceive the bad elements in the situation, or the opposite may occur and the negative material may be denied while only positive elements are retained (the 1.9 and 9.1 positions). At some level of reverberated stress, a person may well switch off completely, seeking to re-repress anxiety by denying the possibility of change. It is this drive which often brings pressure to bear on churches to be islands of no change in a changing world, so effectively containing the congregation in a 1.1. position. Individual ProcessThe process of change begins with ignorance, which may respond to the need for change by withdrawal and denial. As information presses in and motivation rises, polarisation may occur and the individual moves away from the origin, possibly toward the 9.1 position, seeing only the bad things and denying all advantage. Time passes and the internal anxieties are slowly dealt with and worked through. A conversion reaction may set in, in which the position of opposition is exchanged for one of idealised endorsement. From only seeing the bad, a person may move to the position of only seeing the good, and then begin to oscillate, backwards and forwards, with the time spent in each idealised position decreasing. The intensity of idealisation lowers, the oscillation damps down and the person moves to the 5.5 position, beginning to be aware of both good and bad issues, but held in conflicted ambivalence between them. With further work on the underlying anxieties the person moves out along the diagonal from the 5.5 position towards the integration of 9.9. During this period the impending change is gradually accepted, the process of loss and mourning is worked through and moods are often characterised by depression. Hope begins to surface and eventually the person is able to handle the change realistically with a sense of relief and joy.If the change is too sudden for all the emotional work to be handled at the time, and if no provision is made for healthy working through of the disturbance then the person is loaded with yet more internal stress and is less able to respond to future change. If there is no understanding or support during the process, or if the stress levels from other sources suddenly rise, a person may reverse direction and regress to the (1.1) position, either temporarily, or possibly permanently. If the change does go ahead under these circumstances, the person may opt out, resign office, leave the system, or in extreme cases become ill, have a breakdown or die. Social ProcessIf a large group of people, a congregation, or an organisation is facing a particular change, members will be distributed across the grid in various ways. Some will huddle together near the origin, with a spokesperson denying the need for any change. Others will be clustered around the 1.9 position, perceiving no possible objections and impatient to get into action. >In heavy opposition will be a group in the 9.1 position, viewing the proposed change as a potential disaster and seeing their task and loyalty to the institution as demanding total opposition to the suggested course of action. Another group may be caught in the fight between the two extremes, suggesting postponement of the solution, the setting up of another committee, or simply unable to make up their minds. Another small group may act as the mourners, grieving over the loss involved and carrying the depression. Some will be grouped in the 9.9 position, working realistically with the pros and cons of proposals, getting on with the work involved and leading the way forward.The more intense the anxieties raised by the change process, the more intensely polarised and conflicted this social map becomes. If the change process is effectively handled and sufficient time and resources are provided to work through the underlying anxieties, then people are able to flow out from their position near the origin, through the polarisation phase, back into the ambivalence and oscillation, through the depression and mourning and out into the realistic engagement of the 9.9 position. If the process is mishandled the change may be aborted or carried through only at the expense of the secession of a splinter group. Intense conflict may develop, and instead of being discharged creatively, escalate into destructive fighting, with consequent high costs in terms of personal hurt and casualty, expenditure of time and in extreme cases with large social systems, destructive breakdown, scapegoating, rioting, vandalism, terrorism, or war. |